|

|

|

Amazon.com International Sites :

USA, United Kingdom, Germany, France

Books about Crusades :

A History of the Crusades : The Kingdom

of Acre and the Later Crusades

"God wills it!" That was the battle cry of the thousands of Christians who joined crusades to free the Holy Land from the Turks. From 1096 to 1270 there were eight major crusades and two children's crusades, both in the year 1212. Only the First and Third Crusades were successful. In the long history of the Crusades, thousands of knights, soldiers, merchants, and peasants lost their lives on the march or in battle.

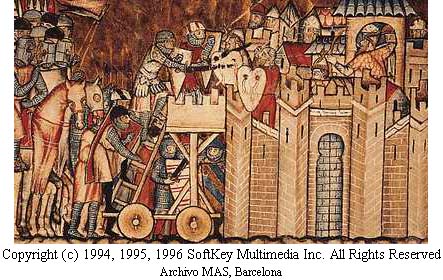

The crusading knights from Europe used all the means of war at their disposal to attack and conquer castles and fortified towns in the Holy Land. --Archivo MAS, Barcelona

To the Christians of Europe, Jerusalem in the Holy Land was a sacred city. The tomb of Christ, the Mount of Olives,

Golgotha, and all places associated with the life and death of Christ were believed to have divine powers of healing

and of absolving penitents of sin. People from all parts of Europe made pilgrimages to Jerusalem and other holy

places.

As long as the Saracens held Jerusalem, there was very little trouble. The Saracens permitted the pilgrims to come

and go. In 1071, however, the fierce Seljuk Turks captured Jerusalem from the Saracens. The Turks at once began

to persecute the Christians. Pilgrims on their way to the Holy City were robbed and beaten. The sacred places of

the Roman Catholic church were profaned or destroyed.

When European Christians heard of the persecution, they were outraged. Alexius Commenus, emperor of the Eastern

Roman Empire, feared that the Turks might seize Constantinople, his capital. They had already defeated and slain

his predecessor. As the terror of the Turks spread, Alexius Commenus sent a plea for aid to Pope Urban II at Rome.

The pope called a council at Clermont in France in 1095. Speaking with ringing eloquence, he urged his audience

to undertake a crusade to rescue the Holy Land. No speech in history has ever had greater results. Fired with religious

zeal, clergy, knights, and common people shouted, "God wills it!"

Preparations began at once for the long, hard journey to Jerusalem. This was the First Crusade, from 1096 to 1099.

Many of the people were so deeply stirred that they would not wait until the time set by the council for starting

the crusade. At least four separate bands started for the Holy Land early in 1096.

One of these was led by a knight named Walter the Penniless. Several thousand followed him through Germany and

Hungary to Constantinople. A monk named Peter the Hermit led other thousands, including whole families, from Germany.

These two "people's crusades" had made no provision for supplies. The people tried to live off the country.

More than half of Peter's followers died or were seized as slaves when they passed into Bulgaria. Most of Walter's

crusaders, and Walter himself, were massacred in ambush by the Turks east of Constantinople.

In August 1096 the first real armies of knights and princes began their march to Jerusalem. They were in four main

companies. Their famous leaders included Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert of Normandy, Raymond of Toulouse, and Bohemond

the Norman.

On the breast of their tunics the crusaders wore a cross of blood-red cloth. Those who returned from the crusade

wore the cross on their backs. The Latin word for cross is crux, and from this word comes the name "crusaders."

From Constantinople the First Crusade made a dangerous march across Asia Minor to Antioch, "city of great

towers." For seven months they besieged the city, suffering almost as much as the Turks penned inside. After

the crusaders at last captured Antioch, they themselves were besieged by a Turkish army. In some three weeks, disease

and famine killed many. The courage of the crusaders faltered.

The almost hopeless situation was saved in a strange way. A priest, Peter Barthelemy, told the leaders of the crusade

that he had dreamed three times of the head of the lance that had pierced the side of Christ. Peter said the head

of the lance was hidden under the high altar of the church. If found, it would bring victory to the crusaders.

Many were skeptical, but Peter found the spear. His discovery, real or feigned, fired the crusaders with valor.

They rushed from the fortified city gate and routed the Turks.

After six months in Antioch, the crusaders set out in June 1099 for Jerusalem. Only a few thousand of the original

tens of thousands remained alive. The rest, however, forgot their sufferings when they saw the Holy City rising

before them. They fell on their knees, kissed the ground, and shouted with tearful gratitude, "Jerusalem,

Jerusalem!"

After several weeks of fighting, the crusaders took Jerusalem on July 15, 1099. Then they engaged in a shameful

massacre of the Turks. After the slaughter, the crusaders walked barefooted and bareheaded to kneel at the Holy

Sepulcher.

Most of the crusaders soon returned home, wearing the victors' crimson cross on their backs. Those who stayed in

the Holy Land were soon joined by new companies of crusaders.

They chose Godfrey of Bouillon as ruler, with the title Defender of the Holy Sepulcher. According to legend, he

refused a crown and the title of king, saying that he "would never wear a crown of gold where his Savior had

worn a crown of thorns." The crusaders built castles and created special orders of knighthood to protect the

Holy Land. The chief orders were the Knights Hospitalers; the Knights Templars; and, later, the Teutonic Order,

sometimes called the Teutonic Knights.

The renewed spread of Muslim power in Asia Minor inspired the Second Crusade (1147-49). St. Bernard of Clairvaux

preached it but refused to lead the expedition. Under Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France, it was so

mismanaged that it accomplished nothing. A great failure, it returned in defeat.

In 1187 the famous Muslim ruler Saladin seized Jerusalem. Unlike the vengeful crusaders in 1099, he did not slay

his defeated foes. He permitted many to go free, some even without ransom.

Saladin's conquest inspired the Third Crusade (1189-91). The leaders were Richard the Lion-Hearted of England,

Philip Augustus of France, and the aged emperor of Germany Frederick Barbarossa, so called because of his red beard.

The German expedition collapsed when Frederick drowned in a mountain stream in Asia Minor on June 10, 1190, while

trying to swim.

Richard the Lion-Hearted and Philip of France took their armies by sea, sailing from the French Mediterranean coast.

When they reached the Holy Land they joined the Christians besieging Acre. After a siege of 23 months, Acre fell

in July 1191. Philip and Richard then quarreled and Philip returned to France. (See also Philip,

Kings of France.)

Richard stayed but could not capture Jerusalem from Saladin. However, he did get a three-year truce from Saladin

in 1192. The truce permitted pilgrims to visit the Holy Sepulcher. (See also Richard,

Kings of England; Saladin.)

The Fourth Crusade (1202-04) was organized to attack the Muslims in Egypt. This meant crossing the Mediterranean

Sea. The crusaders promised to pay the Venetians for ships. When they could not raise enough money, the Venetians

said the crusaders could have ships if they would help to capture Zara. This commercial city on the Adriatic was

a rival of Venice. It was a Christian city, but the crusaders seized it in November 1202.

The ambitious Venetians then suggested that the crusaders help them seize the great Christian city of Constantinople.

Pope Innocent III forbade the expedition, but most of the crusaders went. They took Constantinople in July 1203.

They not only pillaged the magnificent city but also divided the lands of the emperor. This seriously weakened

the Byzantine Empire (see Byzantine Empire). The conquerors then set up a temporary

Latin Empire.

Unlike the other crusades, the Fourth Crusade was not bound for the Holy Land. Nor was it inspired by religious

zeal. Political and commercial greed ruled it.

The two Children's Crusades (1212) were almost unbelievable. The first was led by Stephen of France. Stephen was

a shepherd boy about 12 years old. In the spring of 1212 he said that God had appeared to him in a vision on a

hillside near Cloyes in France. Stephen declared that God had told him only innocent children could drive the infidels

from the Holy Land and had given Stephen a letter for King Philip of France. The king refused permission for a

children's crusade and commanded Stephen to return home.

Instead, Stephen went into the countryside and preached a crusade. His feverish zeal attracted children from all

parts. Few, if any, were over 12 years old; some were girls. A few adults joined them. Singing, shouting, and praying,

they all tramped after Stephen, living off the countryside. Some died on the way, but about 30,000 marched with

Stephen into Marseilles. The ragged, footsore, half-starving youngsters waited there for God to part the waters

of the Mediterranean Sea for their march to Jerusalem.

At last unscrupulous merchants loaded the exhausted little crusaders into old, rotted ships for "free transport

to the Holy Land." Two of the vessels sank in a storm. All aboard drowned. The unhappy children on the other

ships were sold into slavery in Egypt.

Meanwhile news of Stephen's preaching had spread into Germany. It inspired the boy Nicholas to band German children

together to free the Holy Land. He preached that they would not use arms. Instead they would convert the infidels

to Christianity.

Thousands joined him. The German children were somewhat older than the French group. Nicholas led his young crusaders

over the Alps to Rome. Less than a third lived through the dreadful march. At Rome Pope Innocent III gently ordered

them home; but most were too worn out to make the return journey. They took refuge in villages along the way, never

reaching their own homes in Germany.

The Fifth Crusade took place in Egypt (1218-21). By the time of the Sixth Crusade (1228-29), the Muslims were split

and weakened. Frederick II of Sicily, emperor of Germany, freed Jerusalem by peaceful negotiation. In 1244 Turks

seized the Holy City. This led to the Seventh Crusade (1249), headed by Louis IX of France. It tried to take Egypt

as the western key to Palestine, but Louis was captured and forced to pay a "king's ransom." He and Prince

Edward of England led the Eighth Crusade (1270). Louis died of plague and the crusade failed.

This ended the age of the Crusades. By the close of the 13th century the crusading Christians and the knights were

ousted entirely from the Holy Land. Only Christian traders stayed in the Near East.

The chief reason for the Crusades was liberation of the Holy Land. Other causes, however, were also at work. Some

historians regard the Crusades as an early move in the "expansion of Europe."

At the time of the Crusades, Christian Europe was living in the age of feudalism. The lord of the castle ruled

his lands and peasants. There was little town life, except in Italy, and trade was mainly local. But the increasing

population needed expansion of territory and trade. Men hoped to get estates in the East.

Townsmen were increasing in number and influence. The Crusades gave them trade contact with the East. New foods

and textiles began to appear in the markets and fairs of Europe. The new products included cane sugar, buckwheat,

rice, apricots, watermelons, oranges, limes, lemons, cotton, damask, satin, velvet, and dyestuffs.

The East also showed the crusaders a civilization superior to Europe's in many ways. They saw large cities, splendid

buildings, highly developed arts and crafts, medical skills, and scientific knowledge.

The Crusades failed to regain the Holy Land, but their contact with the East awakened Europe to new ways of living

and to new thinking. This led to the Renaissance, the spark of modern Europe (see Renaissance).

Another great result of the Crusades was the Age of Discovery. The Muslims kept Europeans from expanding to the

east, and so they turned westward and finally discovered the New World.

Amazon.com International Sites :