|

|

|

Amazon.com International Sites :

USA, United Kingdom, Germany, France

Books about Greek and Roman Art :

Greek and Roman Art (Fitzwilliam Museum Handbooks)

The art of the ancient Greeks and Romans is called classical art. This name is used also to describe later periods in which artists looked for their inspiration to this ancient style. The Romans learned sculpture and painting largely from the Greeks and helped to transmit Greek art to later ages. Classical art owes its lasting influence to its simplicity and reasonableness, its humanity, and its sheer beauty.

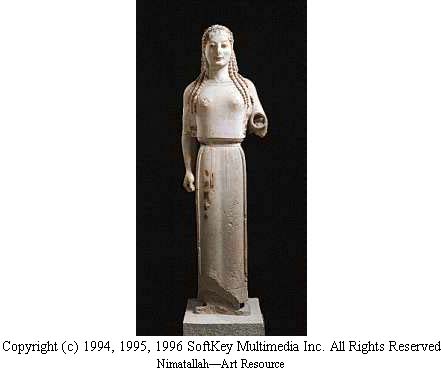

A kore, or freestanding statue of a young woman, was a type of sculpture that originated in about 600 BC and was popular until the end of the Archaic period a century later. This figure is in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. --Nimatallah--Art Resource

Dionysus and Eros in Procession.

Greece, Athenian, mid-4th century BC.

Wine jug, red-figured, Kerch style. Height 24 cm. --The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fletcher Fund, 1925 (25.190)

The first and greatest period of classical art began in Greece about the middle of the 5th century BC. By that

time Greek sculptors had solved many of the problems that faced artists in the early archaic period. They had learned

to represent the human form naturally and easily, in action or at rest. They were interested chiefly in portraying

gods, however. They thought of their gods as people, but grander and more beautiful than any human being. They

tried, therefore, to portray ideal beauty rather than any particular person. Their best sculptures achieved almost

godlike perfection in their calm, ordered beauty.

The Greeks had plenty of beautiful marble and used it freely for temples as well as for their sculpture. They were

not satisfied with its cold whiteness, however, and painted both their statues and their buildings. Some statues

have been found with their bright colors still preserved, but most of them lost their paint through weathering.

The works of the great Greek painters have disappeared completely, and we know only what ancient writers tell us

about them. Parrhasius, Zeuxis, and Apelles, the great painters of the 4th century BC, were famous as colorists.

Polygnotus, in the 5th century, was renowned as a draftsman.

Fortunately we have many examples of Greek vases. Some were preserved in tombs; others were uncovered by archaeologists

in other sites. The beautiful decorations on these vases give us some idea of Greek painting. They are examples

of the wonderful feeling for form and line that made the Greeks supreme in the field of sculpture.

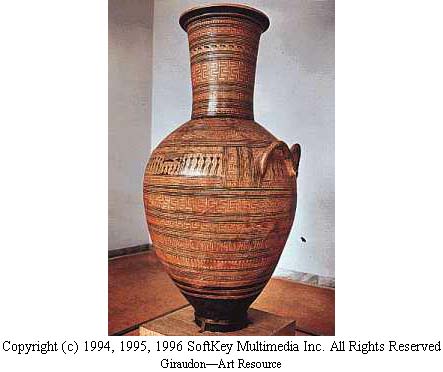

The Dipylon amphora from the geometric period, now in the National Museum of Athens, shows one of the two principal shapes for Greek vessel pottery. --Giraudon--Art Resource

The earliest vases--produced from about the 12th century to the 8th century BC--were decorated with brown paint

in the so-called geometric style. Sticklike figures of men and animals were fitted into the over-all pattern. In

the next period the figures of men and gods began to be more realistic and were painted in black on the red clay.

In the 6th century BC the figures were left in red and a black background was painted in.

By the 8th century BC the Greeks had become a seafaring people and began to visit other lands. In Egypt they saw

many beautiful examples of both painting and sculpture. In Asia Minor they were impressed by the enormous Babylonian

and Assyrian sculptures that showed narrative scenes.

The early Greek statues were stiff and flat, but in about the 6th century BC the sculptors began to study the human

body and work out its proportions. For models they had the finest of young athletes. The Greeks wore no clothing

when they practiced sports, and the sculptor could observe their beautiful, strong bodies in every pose.

Greek religion, Greek love of beauty, and a growing spirit of nationalism found fuller and fuller expression. But

it took the crisis of the Persian invasion (490-479 BC) to arouse the young, virile race to great achievements.

After driving out the invaders, the Greeks suddenly, in the 5th century, reached their full stature. What the Persians

had destroyed, the Greeks set to work to rebuild. Their poets sang the glories of the new epoch, and Greek genius,

as shown in the great creations at Athens, came to full strength and beauty. It was then, under Pericles, that

the Athenian Acropolis was restored and adorned with the matchless Parthenon, the Erechtheum, and other beautiful

buildings. There were beautiful temples in other cities of Greece too, notably that of Zeus at Olympia, which are

known from descriptions by the ancient writers and from a few fragments that have been discovered in recent times.

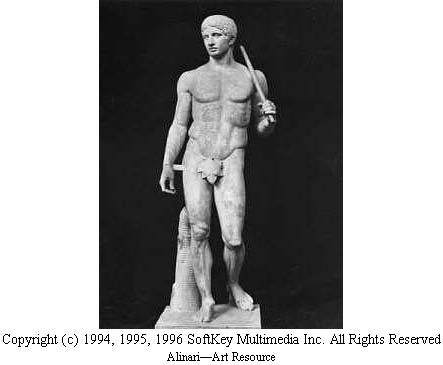

The original 'Doryphorus', or Spear Bearer, done in the style of a Greek school in about 450-40 BC, was probably by Polyclitus. A marble Roman copy pictured, now in the National Museum in Naples, Italy, was modeled on the bronze Greek original. --Alinari--Art Resource

The 5th century BC was made illustrious in sculpture also by the work of three great masters, all known today in

some degree by surviving works. Myron is famous for the boldness with which he fixed moments of violent action

in bronze, as in his famous 'Discobolus', or Discus Thrower. There are fine copies now in Munich and in the Vatican,

in Rome. The 'Doryphorus', or Spear Bearer, of Polyclitus was called by the ancients the Rule, or guide in composition.

The Spear Bearer was believed to follow the true proportions of the human body perfectly.

The greatest name in Greek sculpture is that of Phidias. Under his direction the sculptures decorating the Parthenon

were planned and executed. Some of them may have been the work of his own hand. His great masterpieces were the

huge gold and ivory statue of Athena which stood within this temple and the similar one of Zeus in the temple at

Olympia. They have disappeared. Some of his great genius can be seen in the remains of the sculptures of the pediments

and frieze of the Parthenon. Many of them are preserved in the British Museum. They are known as the Elgin Marbles.

Lord Elgin brought them from Athens in 1801-12.

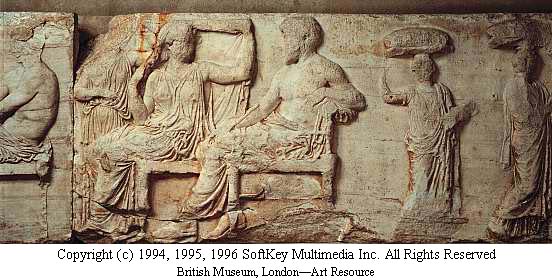

Part of the east frieze of the Parthenon shows Zeus, chief of the gods, seated facing his consort Hera, who holds a bridal veil. The sculpture is from between 447 and 432 BC. --British Museum, London--Art Resource

These sculptures are the greatest works of Greek art that have come down to modern times. The frieze ran like a

decorative band around the top of the outer walls of the temple. It is 3 feet 3 1/2 inches high and 524 feet long.

The subject is the ceremonial procession of the Panathenaic Festival. The figures represent gods, priests, and

elders; sacrifice bearers and sacrificial cattle; soldiers, nobles, and maidens. They stand out in low relief from

an undetailed background. All are vividly alive and beautifully composed within the narrow band. The horses and

their riders are particularly graceful. Their bodies seem to press forward in rhythmical movement.

Around the outside of the portico above the columns were 92 almost square panels known as the metopes. Each panel

depicted two figures in combat.

In the east and west triangular pediments were groups of figures judged to be the world's greatest examples of

monumental sculpture. The problem of composing figures in the triangular space of a low pediment was most skillfully

solved.

The east pediment represented the contest of Athena and Poseidon over the site of Athens. The west pediment illustrated

the miraculous birth of Athena out of the head of Zeus. The use of color and of bronze accessories enhanced the

beauty of the pediment groups.

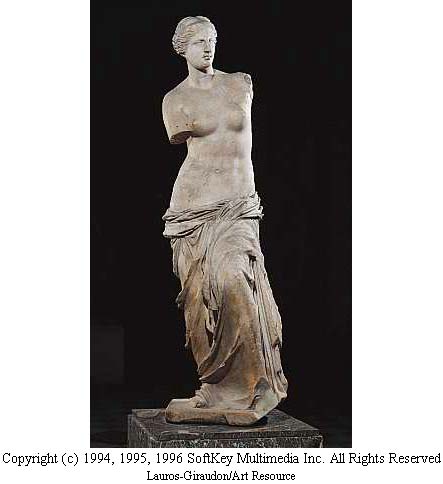

The classic statue of Aphrodite is the world-famous Venus de Milo carved in about 150 BC, now at the Louvre in Paris. --Lauros-Giraudon/Art Resource

The 'Aphrodite' of Melos, commonly known as the 'Venus de Milo', is a beautiful marble statue now exhibited in

the Louvre, Paris. Nothing is known of its sculptor. Experts date it between 200 and 100 BC.

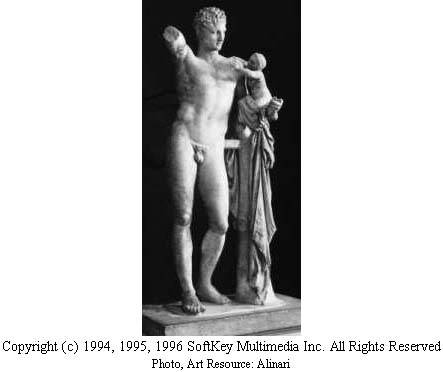

Praxiteles' 'Hermes with the Infant Dionysus' is the only known original by an early Greek master. Unearthed in 1877 at Olympia, Greece, it is in the Olympia Museum. The missing arm probably held a bunch of grapes, toward which the child is reaching. --Photo, Art Resource: Alinari

The works of Phidias were followed by those of Praxiteles, Scopas, and Lysippus. What is believed to be an original

work of Praxiteles, the statue 'Hermes with the Infant Dionysus', is preserved in a Greek museum. This is the only

statue that can be identified with one of the great Greek masters. Most of these sculptors are known only through

copies of their work by Roman artists. The figure of Hermes--strong, active, and graceful, the face expressive

of nobility and sweetness--is most beautiful. The so-called Satyr or Faun of Praxiteles, which suggested Hawthorne's

'Marble Faun', is probably the work of another sculptor of the same school. Praxiteles' sculpture is less lofty

and dignified than that of Phidias, but it is full of grace and charm. Scopas carried further the tendency to portray

dramatic moods, giving his subjects an intense impassioned expression. Lysippus returned to the athletic type of

Polyclitus, but his figures are lighter and more slender, combining manly beauty and strength. He was at the height

of his fame in the time of Alexander the Great, who, it is said, wanted only Lysippus to portray him.

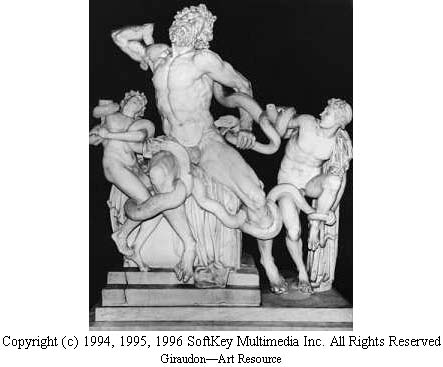

In legend, Laocoon and his sons were crushed to death by serpents for breaking a vow to Apollo. The statue, in the Vatican Museum, is by Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus. --Giraudon--Art Resource

The period following the death of Alexander is known as the Hellenistic. Greek art lost much of its simplicity

and ideal perfection of form, its serenity and restraint, but it gained in intensity of feeling and became more

realistic. Two works of the period are the 'Dying Gaul', sometimes called the 'Dying Gladiator', and the beautiful

'Apollo Belvedere'. The 'Laocoon' group, which depicts a father and his sons crushed to death by serpents, illustrates

the extremity of physical suffering as represented in sculpture.

A famous late Hellenistic statue is the 'Nike', or 'Winged Victory'. The dramatic effect of her sweeping draperies

and the swift movement of the figure are distinctive. In contrast to previous standing figures, this is an action

pose, giving a sense of motion and wind at sea. The date of the statue has been disputed. At present it is usually

placed between 250 and 180 BC. It was discovered in 1863 on the island of Samothrace and is now in the Louvre,

Paris. Excavations on the same site in 1950 uncovered the right hand of the figure. The Greek government gave it

to the Louvre in exchange for a frieze that once adorned a temple on the island.

From early times the Romans had felt the artistic influence of Greece. In 146 BC, when Greece was conquered by

Rome, Greek art became inseparably interwoven with that of Rome. "Greece, conquered, led her conqueror captive"

is the poet's way of expressing the triumph of Greek over Roman culture. The Romans, however, were not merely imitators,

and Roman art was not a decayed form into which Greek art had fallen.

To a large extent the art of the Romans was a development of that of their predecessors in Italy, the Etruscans,

who, to be sure, had learned much from the Greeks (see Etruscans). Nor were the Romans

themselves entirely without originality. Though their artistic forms were, for the most part, borrowed, they expressed

in them, especially in their architecture, their own practical dominating spirit.

In the 2nd century BC the Roman generals began a systematic plunder of the cities of Greece, bringing back thousands

of Greek statues to grace their triumphal processions. Greek artists flocked to Rome to share in the patronage

that was so lavishly bestowed, owing to the rich conquests made as the Roman power was extended. The wealthy Romans

built villas, filled them with works of art in the manner of our modern plutocrats, and called for Greek artists

or Romans inspired by Greek traditions to paint their walls and decorate their courts with sculptures. The ruins

excavated at Pompeii and Herculaneum show us how fond the Romans and their neighbors in Italy were of embellishing

not only their houses, but the objects of daily use, such as household utensils, furniture, etc.

But with the Romans art was used not so much for the expression of great and noble ideas and emotions as for decoration

and ostentation. As art became fashionable, it lost much of its spiritual quality. As they borrowed many elements

of their religion from the Greeks, so the Romans copied the statues of Greek gods and goddesses. The Romans were

lacking in great imagination. Even in one of the few ideal types which they originated, the 'Antinous', the Greek

stamp is unmistakable. In one respect, however, the Roman sculptors did show originality; they produced many vigorous

realistic portrait statues. Among those that have come down to us are a beautiful bust of the young Augustus, a

splendid full-length statue of the same emperor, and busts of other famous statesmen. All these have a historic

as well as an artistic value. So, too, have the reliefs which adorn such structures as the Arch of Titus and the

Column of Trajan, commemorating great events in these emperors' reigns.

A mosaic of a group of musicians was uncovered at Pompeii when the ruins of the city were excavated. Some of the best surviving examples of Roman art have been found preserved by the volcanic ash of Vesuvius in Pompeii and Herculaneum. --Robert Frerck--Odyssey Productions

In painting--though here, too, they learned from the Greeks--it seems probable that the Romans developed more originality

than in sculpture. Unfortunately, as in the case of the Greeks, the great masterpieces of ancient painting no longer

exist; but we can learn much from the mural paintings found in houses at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Rome. The pleasing

coloring, which in many of the paintings still remains fresh and vivid, and the freedom and vigor of the drawing,

would seem to indicate that even from these ancient days Italy was the home of painters of great talent. Portrait

painting especially flourished at Rome, where hack street-corner artists became so common that one could have his

portrait painted for a few cents.

Although the art of Rome loses in comparison with that of Greece, still it commands our admiration, and we owe

the Romans a debt of gratitude for helping to transmit to us the art of the Greeks, who were their great masters.

Amazon.com International Sites :