|

|

|

Amazon.com International Sites :

USA, United Kingdom, Germany, France

Books about Mythology :

The origin of the universe can be explained by modern astronomers and astrophysicists, while archaeologists and historians try to clarify the origin of human societies. In the distant past, however, before any sciences existed, the beginnings of the world and of society were explained by mythology.

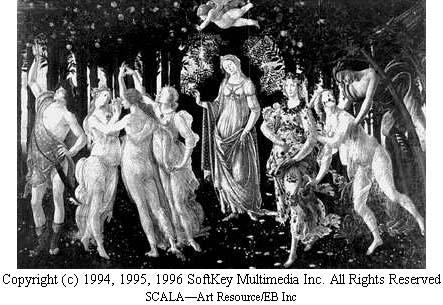

Sandro Botticelli's painting 'Primavera' (Springtime) presents the pregnant figure of Spring in the center. The god Mercury and the three Graces are on the left. On the right are Flora, goddess of flowering plants, and a nymph pursued by the North Wind. --SCALA--Art Resource/EB Inc

The word myth is often mistakenly understood to mean fiction--something that never happened, a made-up story or

fanciful tale. Myth is really a way of thinking about the past. Mircea Eliade, a historian of religions, once stated:

"Myths tell only of that which really happened." This does not mean that myths correctly explain what

literally happened. It does suggest, however, that behind the explanation there is a reality that cannot be seen

and examined.

One of the best-known mythological books is Homer's 'Iliad', which tells of the Trojan War. No one reading the

book today accepts Homer's story as a historically factual account. There is little doubt, however, that at some

time--many centuries before Homer lived--there really was a war between the Greek city-states and the residents

of northwestern Asia Minor. (See also Homeric Legend; Trojan

War.)

Another of the great myths of ancient peoples is the flood legend. The best-known version is the story found in

Genesis, the first book of the Bible, of Noah and his ark. No scientist today would admit that a flood could ever

have covered the whole Earth, with waters reaching higher than the highest mountains. But ancient Mesopotamia experienced

many severe floods. It is likely that one exceptionally devastating flood became the subject of later mythmaking.

Perhaps events from many floods were woven together to make one story (see Flood Legends).

Mythmaking, like superstition, is not the sole property of people who lived thousands of years ago. It has persisted

throughout history. The American West of the 19th century has been a favorite subject on which to build myths.

The West was a reality. There were cowboys, Indians, outlaws, and federal marshals. The stories now presented in

Western fiction and in the movies and on television, however, are highly romanticized versions of a reality that

was far less glamorous.

Mythmaking has traditionally looked to the past to try to make sense out of the present. Some modern myths look

instead to the future. Storytellers make use of the uncountable inventions of the last few centuries to give vivid

depictions of what Earth may be like hundreds of years from now, or they imagine life on worlds billions of light-years

away in space or far in the future.

Myths try to answer several questions. Where did the world come from? What are the gods like, and where did they

come from? How did humanity originate? Why is there evil in the world? What happens to people after they die? Myths

also try to account for a society's customs and rituals. They explain the origins of agriculture and the founding

of cities.

To explain the origins of corn (maize) the Abnaki Indians of North America have handed down a myth in which an

Indian youth encounters a woman with long golden hair. She promises to remain with the man if he follows her instructions.

First, he should make a fire and scorch the ground. Then he must drag her over the burned ground so that her silken

hair can be intertwined with the corn seeds for harvesting. Thus the silky styles on a cornstalk remind new generations

of Indians that she has not forgotten them. Similarly the founding of the city of Rome was told as the myth of

Romulus and Remus, sons of the war god Mars, who were nurtured in infancy by a she-wolf (see Romulus

and Remus).

Beyond giving such explanations, myths are used to justify the way a society lives. Ruling families in several

ancient civilizations found justification for their power in myths that described their origin in the world of

the gods or in heaven. In India the breakdown of society into castes is based on ancient mythology that emerged

in the Indus Valley after 1500 BC.

Myths did not originate in written form. They developed slowly as an oral tradition that was handed down from generation

to generation among people who were trying to make sense of the world around them. They tried to imagine how it

could have come into being in the first place. Fascinated by the small bit of Earth that they knew and by the heavens

above that they saw, they wondered what kind of power could have been responsible for making it all. Furthermore,

the wonders of existence seemed to contrast starkly with human nature and its destructive tendencies. How could

they account for the human condition when they measured it against the grandeur of Earth and sky?

Members of a tribe or clan who were considered wise pondered what they saw and came up with their own conclusions

about what must have happened. They also had to account for everything that had happened from the origin of the

world until their lifetimes. These accounts, passed down in story form, were eventually accepted as traditional

truth. Much later the stories were finally written down.

How comprehensive a developed mythology could become was given written expression in Greece by Hesiod, a poet who

lived in the 9th century BC. His 'Theogony' tells the story of the origin of the gods and of the universe. His

'Works and Days' tells of the previous ages of humanity, beginning with a long-past golden age, and culminates

with the society of his time.

The study by today's astrophysicists of the origin and evolution of the universe is called cosmology. Ancient

stories about the world's origin are called cosmogonic myths, or myths about the birth of the cosmos. As such they

deal not only with the appearance of Earth and the heavens but also with the beginning of everything else--plants,

animals, family, work, sickness, death, evil, and, in some cases, of the gods themselves. The myths and their recitation

became part of the religious ritual of daily life, as they were related to all common and repeated occurrences--the

seasons of the year, the planting and harvesting of crops, the birth of a child, or the death of an adult. Among

Tibetans the solemn recitation of the cosmogonic myth was considered sufficient to cure diseases or imperfections.

By remembering origins, they believed there was a hope of rebirth or revitalization.

Polynesian myth tells how the supreme god, Io, created the world. In the beginning there were only waters and darkness.

By his word and thought Io separated the waters and created Earth and sky. He said: "Let the waters be separated,

let the heavens be formed, let the Earth be." These creative words, the Polynesians believed, were charged

with sacred power and therefore were recited on significant occasions to guarantee the success of an undertaking.

Similarly Australia's aboriginals annually reenacted their myth of origin because they were convinced that the

world, unless periodically renewed, would perish. This theme was also common among the Karok, Hupa, and Yurok Indian

tribes of California. Their ceremony was called a repair, or fixing, of the world.

Creation myths varied a good deal among ancient peoples. A story from India written down in about 700 BC says that

the universe began as the Self in the shape of a man. The Self was lonely, so it divided into two parts--one male

and the other female. From their marriage came the human race. The original two also took the shapes of animals,

and from these first pairs all other animals have descended.

In about 3000 BC the Sumerians in the Middle East had a different account. The god of the waters, Enki, told his

mother, Nammu, to take bits of clay and mold the shapes of men and women. She made perfect people of every sort

to be servants of the gods. Then Enki and his wife, the Earth goddess, had a contest. Each tried to invent people

for whom the other could find no place or task. Thus each created various sorts of deformed and disabled individuals.

This was how the Sumerians explained human imperfections.

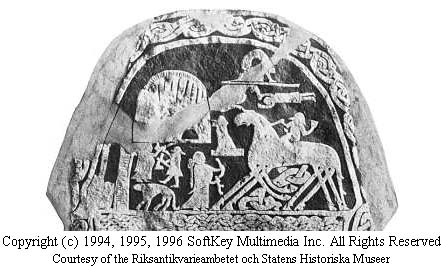

On a funerary stone from about AD 800, Odin, chief of the Norse gods, is shown riding his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir. --Courtesy of the Riksantikvarieambetet och Statens Historiska Museer

In the cold lands of Northern Europe people thought that the first created thing was mist. This mist was said to

have flowed through 12 rivers and froze, filling the vast emptiness of the world with layer upon layer of ice.

Then a warm wind from the south began to melt the ice. Out of the clouds of vapor that arose came two beings--Ymir,

the frost giant, and Audhumla, the cow. When she became hungry, Audhumla got nourishment by licking the frost from

the ice. As she licked the ice she uncovered a manlike form. This was Buri, the first of the gods. His son, Bor,

had three sons--the gods Odin, Vili, and Ve. They killed Ymir, and out of the frost giant's body they made the

rest of the universe. From his eyebrows they made Midgard, the place where humanity was to dwell. Then Odin took

an ash tree and made the first man. The first woman was made from an elm tree.

Numerous legends have tried to explain why human nature was not perfect and why people died. In Western civilization

the best known of these stories is found in the first book of the Bible, Genesis. Some Christians accept the story

as literal history, while others regard it as a parable. In either case the point is the same.

The first two humans, Adam and Eve, lived in a garden and had direct acquaintance with their creator. They were

allowed full use of the garden except for one tree--the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Tempted by a serpent,

Eve ate some of the fruit of the tree and persuaded Adam to do the same. Immediately their original innocence was

lost, and they knew they had been disobedient.

The penalty was expulsion from the garden and eventual death. This legend was recreated in the 17th century by

the English poet John Milton in his classic work 'Paradise Lost'.

In Greek legend the first woman on Earth was Pandora. After Prometheus had stolen fire from heaven and given it

to mankind, Zeus determined to counteract this benefit. He asked Hephaestus, a fire god (Vulcan to the Romans),

to fashion a woman from clay. She opened a jar that released all kinds of evil and misery upon the world (see Pandora).

There is an African myth that explains death as the result of a failed message. God sent a chameleon to deliver

a message that people would be immortal. He also sent a lizard with news that they would die. The chameleon took

his time making the journey and arrived late. The lizard's message of doom was the one that the people received.

Mythmakers likewise tried to explain the end of life and the world. The flood legends were one way of telling

how the Earth was once destroyed--at least all life forms except for a few survivors. In some American Indian myths

the end of the world recurred in a cycle, followed by a new creation. According to ancient Aztec tradition, there

had already been four destructions of the world, and a fifth was expected. Each world was ruled by a sun whose

disappearance marked each ending.

Some mythologies blamed such catastrophic ends of the world on human wickedness. In the Biblical story of Noah

the flood opened the way for a regeneration of the world and a new humanity. Because wickedness persisted, however,

another cataclysm became inevitable. Nearly all modern religions have taken up this kind of mythology, looking

forward to an end of the world, a new creation, and a judgment on humanity for its deeds.

Myths of the end of the universe are integrated with beliefs about death and the fate of humanity afterward. In

many mythologies the dead may be rewarded or punished. It was inconceivable to most ancient peoples that humans

would not survive in some form after death. Egyptian kings made elaborate preparations for the afterlife.

In both Judaism and Christianity, quite complex visions have been devised about the end of the world, the final

judgment, and a new creation. The basis for these ideas is in passages from the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible

(Old Testament), the Book of Revelation in the New Testament, and portions of the Gospels. In contrast to mythologies

of India, the end of the world is supposed to happen only once. There are no cycles of destruction and regeneration.

For Judaism the coming of the Messiah will announce the end of the present world and the restoration of paradise.

For Christianity the end will precede the second coming of Jesus and the last judgment. After these events the

whole universe will be renewed and made perfect. All evil and misfortune will be abolished. Many Christian groups

that have made the doctrine central to their faith have interposed a 1,000-year period, called the millennium,

between the second coming and the end of the world. During this time only the saints will dwell on Earth. Then

Satan will be unleashed to stir up a period of terrible persecution. After that the end will come, followed by

judgment and a new creation. Some groups put the second coming after the millennium. Most traditional Christian

denominations, however, reject the notion of a millennium altogether.

Many ancient religions had what may seem to be a contradictory belief in one Supreme Being and many other gods.

This apparent contradiction was resolved in different ways. Among some primitive peoples it was believed that the

Supreme Being created the world and humanity but soon abandoned the creation and withdrew to the heavens. The lesser

gods were in charge of the world thereafter. In other cases it was believed that the many gods were simply manifestations

of the One. This is the case, for example, in Hinduism.

The mythologies associated with polytheism (belief in many gods) varied among the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and

Teutonic peoples. There were gods for every aspect of nature and of human life. Especially interesting were myths

about young gods, such as Osiris and Adonis, who were murdered but came back to life. From such mythologies developed

the mystery religions of Greece and Rome. These secret cults had common meals and initiation rites that symbolically

celebrated death and resurrection.

One form of mythology was based on the most visible of the heavenly bodies. In some cultures they were considered the eyes of a Supreme Being. Myths of human descent from a sun-god are known among some North American Indian tribes, including the Arapaho and Blackfeet. They are also common in Indonesia and Melanesia. Ruling dynasties in Egypt, Korea, and Japan have also claimed descent from the sun. The moon--because it appears, disappears, and appears again--was believed by some peoples to be the first human who died. In some cases the moon god was viewed as one who had taken the place of a Supreme Being.

Stories about superhuman individuals are common to nearly all ancient civilizations. The best known is probably the Greek legend about Hercules, or Heracles (see Hercules). The Hebrew Bible contains the story of a similar hero, Samson, whose exploits are recorded in the Book of Judges. After he fell in love with Delilah, she learned that his long hair was the secret of his great strength. When he was asleep she cut his hair. He was captured by his enemies, the Philistines, who blinded him and made him their slave. His strength eventually returned, and he destroyed their temple to the god Dagon, killing himself and his captors. In most such myths, after overcoming nearly impossible obstacles, the superhero then belongs to a class of semidivine beings.

| Name | Realm | Also Called |

| Amen | One of the chief Theban deities; united with sun-god under form of Amen-Ra |

Amon, Ammon |

| Anubis | Guide of souls to Amenti, region of dead; son of Osiris; jackal-headed |

|

| Apis | Sacred bull, an embodiment of Ptah; identified with Osiris as Osiris-Apis or Serapis |

|

| Bast | Goddess of Music | Bastet |

| Geb | Earth god; father of Osiris; represented with a goose on his head |

Keb, Seb |

| Hathor | Goddess of love and mirth; cow-headed | Athor |

| Horus | God of day; son of Osiris and Isis; hawk-headed |

|

| Isis | Goddess of motherhood and fertility; sister and wife of Osiris |

|

| Khepera | God of morning sun | |

| Khnemu | Ram-headed god | Khnum, Chnuphis, Chnemu, Chnum |

| Khonsu | Son of Amen and Mut | Khensu, Khuns |

| Ma‘at | Goddess of law, justice, and truth | |

| Mentu | Solar deity, sometimes considered god of war; falcon-headed |

Ment |

| Min | God of fertility | |

| Mut | Wife of Amen | Maut |

| Nekhbet | Protector of childbirth | |

| Nephthys | Goddess of the dead; sister and wife of Set | |

| Nu | Chaos from which the world was created, personified as a god |

|

| Nut | Goddess of heavens; consort of Geb | |

| Osiris | God of the underworld and judge of dead; son of Geb and Nut |

|

| Ptah | Chief deity of the city of Memphis | Phtha |

| Ra | God of the sun, the supreme god; son of Nut; pharaohs claimed descent from him; represented as a lion, a cat, or a falcon |

|

| Sekhmet | Warlike sun-goddess | |

| Serapis | God uniting attributes of Osiris and Apis | |

| Set | God of darkness or evil; brother and enemy of Osiris |

Seth |

| Shu | Solar deity; son of Ra and Hathor | |

| Tem | Solar deity | Atmu, Atum, Tum |

| Thoth | God of wisdom and magic; scribe of the gods; ibis-headed |

Dhouti |

In Egyptian mythology, the dead are judged by the jackal-headed god, Anubis, who weighs the heart of the deceased against the figure of Ma'at, personification of justice, as Osiris, god of the dead, looks on. This funerary papyrus from Thebes dates from about 1025 BC. --Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Excavations, 1928-29, and Rogers Fund, 1930

As they had different forms, the gods also personified different powers. Horus, a god in the form of a falcon,

symbolized the sun and came to represent the pharaoh. Thoth, the moon god, was also the god of time because the

phases of the moon were used to calculate the months. Powers of nature were symbolized by Ra, the sun-god; Nut,

the sky goddess; and Geb, the Earth god. For a time Amenhotep IV made the sun, under the name Aton, the sole god.

Anubis, in the form of a dog, was god of the dead, Ptah was the creator, and Min was a god of fertility. Other

major gods and goddesses included Bast, goddess of music; Isis, queen of the gods; Ma'at, the goddess of law, justice,

and truth; Nekhbet, the protector of childbirth; Osiris, a fertility god, giver of civilization, and ruler of the

dead; Sekhmet, a warlike sun-goddess; and Shu, the god of light and air who supported the sky.

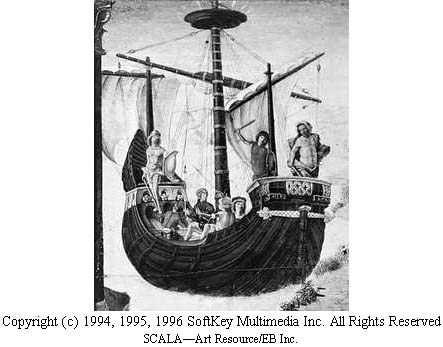

In Greek legend Jason and his band of Argonauts sailed to Colchis on the Black Sea to find the Golden Fleece in order to regain his throne at Iolcus in Thessaly. --SCALA--Art Resource/EB Inc.

The legends of ancient Greece are more familiar because they have become so permanently embedded in literary traditions

of Western civilization. Greek mythology followed the pattern of other mythologies: the forces of nature were given

personalities and were worshiped. There was no worship of animals or of gods in animal form, however, as there

was in Egypt. Pan, for example, had a goat's horns, hoofs, and tail, but his head was like that of a man. Greek

gods and goddesses were pictured as being much like men and women. The term for this is anthropomorphism, meaning

"in the form of a human." The gods were conceived as more heroic in stature, more outstanding in beauty

and proportion, and more powerful and enduring than humans. They were nevertheless endowed with many human weaknesses.

They could be jealous, envious, spiteful, and petty. Among them only Zeus was known as the Just (see Zeus).

The Greeks believed that their gods lived on Mount Olympus. They dwelt together in a community of light and pleasantness,

and from this height they mingled with (and often interfered with) the lives of mortals.

Before the gods existed there had been Titans--the children of Earth (Gaea) and the heavens (Uranus). According

to Hesiod's account there were originally 12 of them: the brothers Oceanus, Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, and

Cronus and the sisters Thea, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, and Tethys. At their mother's prompting they rebelled

against their father, who had shut them off in the underworld of Tartarus. Under the leadership of Cronus they

deposed Uranus and made Cronus their ruler.

Zeus, a son of Cronus, overthrew his father and seized power after a ten-year struggle. The Titans were again imprisoned

in Tartarus. Zeus, also called the Thunderer, was then the first and most powerful of the gods. He ruled the universe

with 11 other gods. Poseidon, his brother, governed the waters. Hades, later called Pluto, ruled the underworld

and the dead. Hestia, sister of Zeus, was goddess of the household. Hera, the wife of Zeus, was the goddess of

marriage, and Ares, a son of Zeus, was the god of war. Athena was the favorite daughter of Zeus (see Athena).

Because she had sprung full grown from his forehead, she was the goddess of wisdom.

Another son of Zeus, Apollo, drove the chariot of the sun across the skies (see Apollo).

He was also the music maker and the god of light and song, and he was worshiped by the poets. His sister Aphrodite

was the goddess of love (see Aphrodite). Hermes, the messenger of the gods, was another

son of Zeus. Hephaestus was the god of fire. The only one of the gods who was not beautiful, he was skilled in

craftsmanship and forged the armor of the gods. He was the patron of handicrafts and the protector of blacksmiths.

Artemis, the twin sister of Apollo, was the moon goddess. The favorite among rural people, she was also goddess

of vegetation, and, attended by nymphs (naiads), supervised waters and lush wild growth. Also the goddess of wild

animals and the hunt, she was often pictured with a stag or a hunting dog.

These were the 12 major gods. There were other lesser ones whom the Greeks worshiped. Demeter, for instance, was

the goddess of grain. Her legend centered on the story of her daughter Persephone, who was stolen by Hades and

taken to live in the underworld. Demeter heard her daughter's cries, but no one knew where she had been taken.

Because Demeter was distressed by Persephone's disappearance, she lost interest in the harvest, and as a result

there was widespread famine. When Apollo traveled under the Earth as he did over it, he saw Persephone in the underworld.

Then Zeus sent Hermes to bring Persephone back. Hades knew he must obey Zeus, but because Persephone had eaten

one pomegranate seed in the land of the dead she had to return there for four months of every year. Each year when

her daughter returned, Demeter made the Earth bloom and bear fruit again. Through this story the Greeks interpreted

the miracle of spring. After Persephone returned to Hades in the fall, winter arrived.

Dionysus was the god of wine. He was a nature god of fruitfulness and vegetation. Lavish festivals called Dionysia

were held in his honor. He came to represent the irrational side of human nature, while Apollo represented order

and reason. The attendants of Dionysus were the satyrs, minor gods representing the forces of nature. They were

depicted with bodies of animals and had small horns and tails like a goat's. Similar in appearance to the satyrs

was Pan, a god who did not live on Mount Olympus. Instead he guarded the flocks while playing his pipes.

The Muses, from whose name the word music is derived, were nine goddesses who came to be regarded as patrons of

the arts and sciences. Their names and the endeavors they inspired were: Clio, history; Calliope, epic poetry;

Erato, love poetry; Euterpe, lyric poetry; Melpomene, tragedy; Polyhymnia, song, rhetoric, and geometry; Thalia,

comedy; Terpsichore, dancing; and Urania, astronomy and astrology.

Perhaps the most threatening of the goddesses were the Fates, called collectively Moirai. There were three Fates,

whom Homer called "spinners of the thread of life." Clotho was the spinner of the thread, hence she was

also a birth goddess. Lachesis measured the length of the thread, the amount of time allotted to each person. And

Atropos cut the thread. These three had more power than most other gods, and whoever resisted them had to face

Nemesis, the goddess of justice.

Hypnos was the god of sleep and brother of Thanatos (Death). The son of Hypnos was Morpheus, the god of dreams.

Thanatos was not worshiped as a god. Homer refers to him as a son of Nyx (Night). Hesiod declared that he was hated

by the gods because he was the personification of death.

The basic mythology of Rome was borrowed from the Greeks, though later Romans also borrowed from the Egyptians

and some of the religions of Asia Minor and the Middle East as the size of the Roman Empire increased. When the

Romans took over the Greek gods, they gave them different names and sometimes combined them with other gods of

their own.

The Romans changed the names of ten of the 12 gods of Mount Olympus to Jupiter (Zeus), Juno (Hera), Neptune (Poseidon),

Vesta (Hestia), Mars (Ares), Minerva (Athena), Venus (Aphrodite), Mercury (Hermes), Diana (Artemis), and Vulcan

(Hephaestus). Apollo and Pluto kept their Greek names, but Pluto was not referred to as Hades by the Romans.

The Romans also continued to worship vague powers called the Numina, but these were not thought of as having shape

or form. One of the Numina was Janus, the god of doorways and of good beginnings. He was sometimes portrayed as

facing in two opposite directions. He was often the first god whose name was invoked in worship rituals. The month

of January was named for him.

Each family had its own god, or Lar. Originally gods of cultivated fields, the Lares were worshiped by each household

at the crossroads where its property joined that of others. Later they were worshiped in houses in association

with the Penates, gods of the storeroom. The state also had its Lares--patrons and protectors of the city who were

depicted as men wearing military cloaks, carrying lances, and seated with a dog (the symbol of watchfulness) nearby.

Also associated with the household cult was Vesta, goddess of the hearth. The lack of an easy source of fire in

ancient communities placed a special premium on the perpetually burning fire in the hearth, or fireplace. The state

worship of Vesta was elaborate. Her shrine was usually in a round building built as a symbolic representation of

a hearth. The shrine in the Forum at Rome had a perpetual fire that was renewed every year on March 1, the day

of the Roman new year. The fire was attended by six priestesses, called Vestal Virgins, who were chosen from girls

between the ages of 6 and 10. They served for 30 years, after which they were free to marry.

The Romans worshiped the goddess of grain as Ceres (origin of the word cereal). Her cult of worship was adopted

from the Greek colony of Cumae from which the Romans imported grain. Cumae also played a major role in the introduction

of the cult of Apollo to Rome. Much later the Emperor Augustus made Apollo his patron.

Augustus also began the cult of the emperor. His assumption of the title Augustus (his real name was Octavian)

helped prepare the way for his being declared a god after his death. This tradition had its roots in the Greek

belief that if someone bestowed gifts worthy of a god, he should be treated as one. Later the imperial cult became

standardized as emperors, no matter how monstrous, declared deification their right. (See also Augustus.)

In the Greek city-states, cults centering around the worship of a particular god developed very early. Some were

local in scope, but after Greece was absorbed into the Roman Empire many of these cults spread throughout the Mediterranean

world and attracted large followings. In time some of the gods and goddesses of the Middle East and Egypt also

had cults built around them. The mystery religions, or mysteries, reached their peak in the first three centuries

AD. After that time Christianity became the dominant religion of the empire, and the mysteries declined.

One of the most widespread of the cults in pre-Roman Greece was devoted to Dionysus. Because he was the god of

wine, his festivals were lively affairs that offered the chance to put aside temporarily the daily routines of

life and get caught up in wild celebrations. In many cases only those who had been initiated into the cult could

participate in the festivities.

The most famous of the secret religious rites of ancient Greece were the Eleusinian mysteries. They were originally

confined to the city of Eleusis, about a day's journey from Athens. In the ritual the search by the earth goddess

Demeter for her abducted daughter Persephone was reenacted. The ritual symbolized the grain being buried in the

soil and growing again to be made into bread. It also carried the message that out of every grave a new life grows,

and thus it promoted a message of the hope for immortality through symbolism that was very close to the Christian

idea of resurrection.

The Orphic mysteries got their name from Orpheus, the Greek hero endowed with superhuman musical skills. According

to legend he was the author of a body of writings called the Orphic rhapsodies, which dealt with purification from

sin and the afterlife. Cult members believed that the human soul was divine, and it was the believer's task to

liberate it from the body. This could be achieved by abstaining from meat, wine, and sex. The soul would come to

judgment after death. If the person had lived properly, the soul would be sent to a paradise called Elysium. If

not, it would be punished and perhaps sent to hell. After either the reward of Elysium or the punishment of hell,

the soul would return to Earth in another body. This cycle of birth and death had to be repeated three times before

the soul was finally released from the cycle.

In all of the mysteries candidates for initiation took an oath of secrecy. They then confessed--in the presence

of the community of believers--all the faults of their lives up to that point. After this a rite of baptism was

performed, which washed away the candidate's sins. The initiation ceremonies symbolized death and resurrection,

and they were usually quite extravagant. In some cults the initiates were enclosed in a tomb and released. In others

they were symbolically drowned or otherwise put to death.

The cults, such as those of Demeter and Dionysus, had seasonal festivals based on the sowing and reaping of grain

or the production of wine. The festivals of the Isis cult were connected with the three Egyptian seasons and with

the cycle of the Nile River--flooding, sowing, and reaping. In the religion of the sun-god the festival was determined

by astronomy. The greatest celebration was on December 24-25 in connection with the winter solstice. The lengthening

of days afterward symbolized the rebirth of the god and the renewal of life. Christianity eventually replaced this

festival with Christmas.

In some of the mysteries there was a tendency to monotheism--belief in one god. Isis, for example, was held to

be the essence of all goddesses; and Sarapis, originally an Egyptian sun-god, was a name uniting the gods into

one. In the religion of the sun-god, a doctrine was developed to show that all gods were only names for the one

god, Sol.

In the cold lands of Northern Europe, a mythology developed that did not emphasize in its gods the beauty and proportion

of the Greek and Roman deities. Odin, the chief god, had only one eye; and Tyr, the god of war, had but one arm.

The rugged landscape, the towering mountains, the long dark winter nights, and the endless struggle against ice

and cold went into the development of Norse mythology.

Buri, the first god, was the grandfather of Odin. Ymir fathered a race of frost giants who were enemies of the

gods. Ymir grew so large and so evil that Odin and his brothers could no longer live with him. They killed him,

and the blood gushed from his body in such torrents that all the giants--except Bergelmer and his wife--were killed.

These two took refuge on a chest and came to the shores of Jotunheim. From them another race of frost giants was

born.

The gods made the Earth from Ymir's body. From it they cut the deep valleys, made the high mountains, and dug the

fjords. From Muspelheim (a hot, glowing land of fire in the south) they caught flying sparks and fastened them

in the heavens as stars. Out of Ymir's eyebrows they built a wall around the place where human beings were to live.

Then the gods made man from an ash tree and woman from an elm and set them to live in this place, called Midgard.

The gods chose as their home a plain named Ida, where they built a city named Asgard. Odin was the father-god,

a counterpart of the Greek Zeus and the Roman Jupiter. He was also called Wotan, or Woden. From his name the day

of the week Wednesday was derived. From the earliest times he was regarded as a war god and the protector of fallen

heroes. His magical horse Sleipnir had eight legs and was able to gallop through the air and over the seas.

There was about Odin a special compassion and sadness. He gained his great wisdom at the price of one eye. Mimir,

the giant who guarded the well of wisdom, would give Odin no drink unless he surrendered an eye. All the skill

and knowledge that Odin won he shared with the gods and mankind. He passed much time in Valhalla, where the great

heroes were brought to feast with him after they died in battle.

Thor, for whom Thursday was named, was the Thunderer. His hammer, Mjollnir, had remarkable qualities, such as the

ability to return to the thrower like a boomerang. His chief enemy was the serpent Jormungand, the symbol of evil.

Having failed to kill the serpent, the gods were destined to fight and kill each other at the end of the world,

called the Ragnarok--the Twilight of the Gods.

Tyr, after whom Tuesday was named, was the god of war and treaties. He was also the god of justice and the guardian

of oaths and guarantor of good faith. Balder was the beautiful god of light. Most of the legends about him concern

his death. The gods often amused themselves by throwing objects at him, knowing he was immune from harm. Balder

was killed when the blind god Hod threw mistletoe--the only thing that could hurt him.

Frey was the god of sun and rain, the patron of bountiful harvests. Freyja was the goddess of love and beauty.

Frigga was Odin's wife and Balder's mother. Friday was named after her. Hel was the goddess of death. Loki was

the evil one, half human and half god. Heimdal was the keeper of the rainbow bridge over which the gods passed

from Asgard to Earth.

The Norse gods were deities who knew intense suffering. For example, they lived with the knowledge that in the

Twilight of the Gods they would go down to defeat under the frost giants. Nevertheless, they also lived in the

belief that heroic action was the highest good. This foreknowledge of doom gave to Norse mythology a tragic nobility

found in no other.

Their Valhalla, unlike the Christian heaven, was not an eternal abode for all who lived good lives on Earth. It

was one of the 12 realms of Asgard, the home of the gods until the Ragnarok. Then they would march out with Odin

to do battle with the giants. The heroes were brought to Valhalla after they died to prepare for this climactic

struggle. The Valkyries, warlike maidens, carried the slain heroes from the field of battle to Asgard. These maidens

served Odin, but their chief duty was to preside over battles and decide who would live or die. At the head of

the feast in Valhalla sat Odin with a raven on each shoulder. One was Huginn (Thought) and the other Muninn (Memory).

These were his messengers from the world.

The ancient Chinese believed that the world was ruled by a power named Heaven, who was considered the husband of

Earth (much as Uranus and Gaea were husband and wife in Greek myth). Other gods and goddesses living below Heaven

were in charge of the sun, moon, planets, wind, fire, rain, and other elements. In addition, certain people who

did especially noteworthy deeds became gods. One was the emperor who taught the art of agriculture. Another was

the woman who taught the techniques of breeding silkworms. The great philosopher Confucius was also considered

a god. After Buddhism was introduced into China from India, many of its saints were accepted as gods.

Both the Chinese and the Koreans worshiped ancestors in the belief that the dead could help them. Koreans also

worshiped nature and prayed to the sun-god Tankun as the founder of their kingdom.

The Japanese also claimed to have descended from the sun. According to their creation myth the Earth was at first

a shapeless mass. Then the god Izanagi and the goddess Izanami were given the job of stirring the formless mass

with a long, jeweled spear. As they stirred, the mixture thickened and dropped off the point of the spear and hardened

into an island. On the island the god and goddess were married and had children. These offspring included the eight

islands of Japan, many gods and goddesses, and finally the sun-goddess Amaterasu. From her descended a series of

god-like and then human emperors.

The first written record of Greek mythology is found in Homer's 'Iliad' and 'Odyssey' (see Homeric

Legend). The 'Iliad' is the story of the Trojan War and the involvement of the gods in it. The 'Odyssey' recounts

Odysseus' voyage home from the war. A century or more after Homer, the poet Hesiod wrote of the history of the

gods in his 'Theogony' and told of the past and present ages of mankind in 'Works and Days'. The Greek dramatists--Aeschylus,

Sophocles, and Euripides--incorporated much mythological material into their plays. Much later the Roman poet Ovid

retold the stories of Greek gods for the education of his countrymen. Rome also had its epic in the 'Aeneid' of

Virgil (see Aeneas).

The Norse 'Poetic (or the Elder) Edda' consists of fragments about the gods and about two heroic families--the

Volsungs and the Nibelungs. Its origins date from the pre-Christian culture of Iceland. Later Snorri Sturluson

wrote 'Prose (or the Younger) Edda'. The story of the Nibelungs became the basis of an early Germanic mythology.

A fragment of Icelandic mythology found its way to the British Isles and took the form of 'Beowulf'.

Bennett, J.C. Of Men and Gods

Edith Hamilton. Mythology

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion

.

Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of

God: Oriental Mythology

Crossley-Holland, Kevin. The

Norse Myths

Detienne, Marcel. The Creation

of Mythology

Gimbutas, Marija. Goddesses and

Gods of Old Europe, 7000 to 3500 BC

Grimal, Pierre. Dictionary of

Classical Mythology

Harris, Geraldine. Gods and Pharaohs

from Egyptian Mythology

Amazon.com International Sites :