|

|

|

Amazon.com International Sites :

USA, United Kingdom, Germany, France

Books about Ancient Greece :

The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient

Greece

"The glory that was Greece," in the words of Edgar Allan Poe, was short-lived and confined to a very

small geographic area. Yet it has influenced the growth of Western civilization far out of proportion to its size

and duration. The Greece that Poe praised was primarily Athens during its golden age in the 5th century BC. Strictly

speaking, the state was Attica; Athens was its heart. The English poet John Milton called Athens "the eye

of Greece, mother of arts and eloquence." Athens was the city-state in which the arts, philosophy, and democracy

flourished. At least it was the city that attracted those who wanted to work, speak, and think in an environment

of freedom. In the rarefied atmosphere of Athens were born ideas about human nature and political society that

are fundamental to the Western world today.

Athens was not all of Greece, however. Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, and Thessalonica were but a few of the many other

city-states that existed on the rocky and mountainous peninsula at the southern end of the Balkans. Each city-state

was an independent political unit, and each vied with the others for power and wealth. These city-states planted

Greek colonies in Asia Minor, on many islands in the Aegean Sea, and in southern Italy and Sicily.

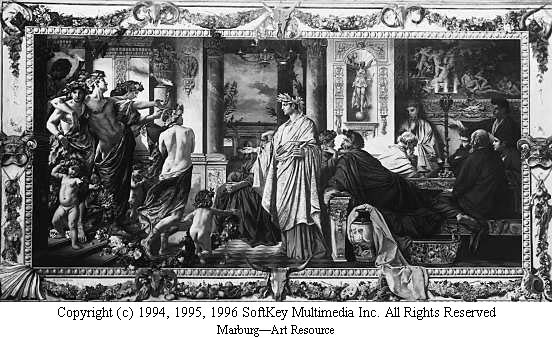

'Plato's Symposium', a painting done in 1869 by Anselm Feuerbach, idealizes the philosophical strivings of ancient Greece. The painting is now in the Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, Germany. --Marburg--Art Resource

The story of ancient Greece began between 1900 and 1600 BC. At that time the Greeks--or Hellenes, as they called

themselves--were simple nomadic herdsmen. Their language shows that they were a branch of the Indo-European-speaking

peoples. They came from the grasslands east of the Caspian Sea, driving their flocks and herds before them. They

entered the peninsula from the north, one small group after another.

The first invaders were the fair-haired Achaeans of whom Homer wrote. The Dorians came perhaps three or four centuries

later and subjugated their Achaean kinsmen. Other tribes, the Aeolians and the Ionians, found homes chiefly on

the islands in the Aegean Sea and on the coast of Asia Minor.

The land that these tribes invaded--the Aegean Basin--was the site of a well-developed civilization. The people

who lived there had cities and palaces. They used gold and bronze and made pottery and paintings (see Aegean

Civilization).

The Greek invaders were still in the barbarian stage. They plundered and destroyed the Aegean cities. Gradually,

as they settled and intermarried with the people they conquered, they absorbed some of the Aegean culture.

Little is known of the earliest stages of Greek settlement. The invaders probably moved southward from their pasturelands

along the Danube, bringing their families and primitive goods in rough oxcarts. Along the way they grazed their

herds. In the spring they stopped long enough to plant and harvest a single crop. Gradually they settled down to

form communities ruled by kings and elders.

The background of the two great Greek epics--the 'Iliad' and the 'Odyssey'--is the background of the Age of Kings

(see Homeric Legend). These epics depict the simple, warlike life of the early Greeks.

The Achaeans had excellent weapons and sang stirring songs. Such luxuries as they possessed, however--gorgeous

robes, jewelry, elaborate metalwork--they bought from the Phoenician traders (see Phoenicians).

The 'Iliad' tells how Greeks from many city-states-- among them, Sparta, Athens, Thebes, and Argos-- joined forces

to fight their common foe Troy in Asia Minor (see Trojan War). In historical times

the Greek city-states were again able to combine when the power of Persia threatened them. However, ancient Greece

never became a nation. The only patriotism the ancient Greek knew was loyalty to his city. This seems particularly

strange today, as the cities were very small. Athens was probably the only Greek city-state with more than 20,000

citizens.

Just as Europe, unlike North America, is divided into many small nations rather than a few large political units,

so ancient Greece was divided into many small city-states. Sometimes the Greek city-states were separated by mountain

ranges. Often, however, a single plain contained several city-states, each surrounding its acropolis, or citadel.

These flattopped, inaccessible rocks or mounds are characteristic of Greece and were first used as places of refuge.

From the Corinthian isthmus rose the lofty acrocorinthus, from Attica the Acropolis of Athens, from the plain of

Argolis the mound of Tiryns, and, loftier still, the Larissa of Argos. On these rocks the Greek cities built their

temples and their king's palace, and their houses clustered about the base.

Only in a few cases did a city-state push its holdings beyond very narrow limits. Athens held the whole plain of

Attica, and most of the Attic villagers were Athenian citizens. Argos conquered the plain of Argolis. Sparta made

a conquest of Laconia and part of the fertile plain of Messenia. The conquered people were subjects, not citizens.

Thebes attempted to be the ruling city of Boeotia but never quite succeeded.

Similar city-states were found all over the Greek world, which had early flung its outposts throughout the Aegean

Basin and even beyond. There were Greeks in all the islands of the Aegean. Among these islands was Thasos, famous

for its gold mines. Samothrace, Imbros, and Lemnos were long occupied by Athenian colonists. Other Aegean islands

colonized by Greeks included Lesbos, the home of the poet Sappho; Scyros, the island of Achilles; and Chios, Samos,

and Rhodes. Also settled by Greeks were the nearer-lying Cyclades--so called (from the Greek word for "circle")

because they encircled the sacred island of Delos--and the southern island of Crete.

The western shores of Asia Minor were fringed with Greek colonies, reaching out past the Propontis (Sea of Marmara)

and the Bosporus to the northern and southern shores of the Euxine, or Black, Sea. In Africa there were, among

others, the colony of Cyrene, now the site of a town in Libya, and the trading post of Naucratis in Egypt. Sicily

too was colonized by the Greeks, and there and in southern Italy so many colonies were planted that this region

came to be known as Magna Graecia (Great Greece). Pressing farther still, the Greeks founded the city of

Massilia, now Marseilles, France.

Separated by barriers of sea and mountain, by local pride and jealousy, the various independent city-states never

conceived the idea of uniting the Greekspeaking world into a single political unit. They formed alliances only

when some powerful city-state embarked on a career of conquest and attempted to make itself mistress of the rest.

Many influences made for unity--a common language, a common religion, a common literature, similar customs, the

religious leagues and festivals, the Olympic Games--but even in time of foreign invasion it was difficult to induce

the cities to act together.

The government of many city-states, notably Athens, passed through four stages from the time of Homer to historical

times. During the 8th and 7th centuries BC the kings disappeared. Monarchy gave way to oligarchy--that is, rule

by a few. The oligarchic successors of the kings were the wealthy landowning nobles, the "eupatridae,"

or wellborn. However, the rivalry among these nobles and the discontent of the oppressed masses was so great that

soon a third stage appeared.

The third type of government was known as tyranny. Some eupatrid would seize absolute power, usually by promising

the people to right the wrongs inflicted upon them by the other landholding eupatridae. He was known as a "tyrant."

Among the Greeks this was not a term of reproach but merely meant one who had seized kingly power without the qualification

of royal descent. The tyrants of the 7th century were a stepping-stone to democracy, or the rule of the people,

which was established nearly everywhere in the 6th and 5th centuries. It was the tyrants who taught the people

their rights and power.

By the beginning of the 5th century BC, Athens had gone through these stages and emerged as the first democracy

in the history of the world. Between two and three centuries before this, the Athenian kings had made way for officials

called "archons," elected by the nobles. Thus an aristocratic form of government was established.

About 621 BC an important step in the direction of democracy was taken, when the first written laws in Greece were

compiled from the existing traditional laws. This reform was forced by the peasants to relieve them from the oppression

of the nobles. The new code was so severe that the adjective "draconic," derived from the name of its

compiler, Draco, is still a synonym for "harsh." Unfortunately, Draco's code did not give the peasants

sufficient relief. A revolution was averted only by the wise reforms of Solon, about a generation later (see Solon). Solon's reforms only delayed the overthrow of the aristocracy, and about 561 BC Pisistratus,

supported by the discontented populace, made himself tyrant. With two interruptions, Pisistratus ruled for more

than 30 years, fostering commerce, agriculture, and the arts and laying the foundation for much of Athens' future

greatness. His sons Hippias and Hipparchus attempted to continue their father's power. One of them was slain by

two youths, Harmodius and Aristogiton, who lived on in Greek tradition as themes for sculptors and poets. By the

reforms of Clisthenes, about 509 BC, the rule of the people was firmly established.

Very different was the course of events in Sparta, which by this time had established itself as the most powerful

military state in Greece (see Sparta). Under the strict laws of Lycurgus it had maintained

its primitive monarchical form of government with little change (see Lycurgus). Nearly

the whole of the Peloponnesus had been brought under its iron heel, and it was now jealously eyeing the rising

power of its democratic rival in central Greece.

During this period the intellectual and artistic culture of the Greeks centered among the Ionions of Asia Minor.

Thales, called "the first Greek philosopher," was a citizen of Miletus. He became famous for predicting

an eclipse of the sun in 585 BC.

Suddenly there loomed in the east a power that threatened to sweep away the whole promising structure of the new

European civilization. Persia, the great Asian empire of the day, had been awakened to the existence of the free

peoples of Greece by the aid which the Athenians had sent to their oppressed kinsmen in Asia Minor. The Persian

empire mobilized its gigantic resources in an effort to conquer the Greek city-states. The scanty forces of the

Greeks succeeded in driving out the invaders (see Persian Wars).

From this momentous conflict Athens emerged a blackened ruin yet the richest and most powerful state in Greece.

It owed this position chiefly to the shrewd policies of the statesman Themistocles, who had seen that naval strength,

not land strength, would in the future be the key to power. "Whoso can hold the sea has command of the situation,"

he said. He persuaded his fellow Athenians to build a strong fleet--larger than the combined fleets of all the

rest of Greece--and to fortify the harbor at Piraeus.

The Athenian fleet became the instrument by which the Persians were finally defeated, at the battle of Salamis

in 480 BC. The fleet also enabled Athens to dominate the Aegean area. Within three years after Salamis, Athens

had united the Greek cities of the Asian coast and of the Aegean islands into a confederacy (called the Delian

League because the treasury was at first on the island of Delos) for defense against Persia. In another generation

this confederacy became an Athenian empire.

Almost at a stride Athens was transformed from a provincial city into an imperial capital. Wealth beyond the dreams

of any other Greek state flowed into its coffers--tribute from subject and allied states, customs duties on the

flood of commerce that poured through Piraeus, and revenues from the Attic silver mines. The population increased

fourfold or more, as foreigners streamed in to share in the prosperity. The learning that had been the creation

of a few "wise men" throughout the Greek world now became fashionable. Painters and sculptors vied in

beautifying Athens with the works of their genius. Even today, battered and defaced by time and man, these art

treasures remain among the greatest surviving achievements of human skill. The period in which Athens flourished,

one of the most remarkable and brilliant in the world's history, reached its culmination in the age of Pericles,

460-430 BC (see Pericles). Under the stimulus of wealth and power, with abundant leisure

and free institutions, the citizen body of Athens attained a higher average of intellectual interests than any

other society before or since.

It must be remembered, however, that a very large part of the population was not free, that the Athenian state

rested on a foundation of slavery. Two fifths (some authorities say four fifths) of the population were slaves.

Slave labor produced much of the wealth that gave the citizens of Athens time and money to pursue art and learning

and to serve the state.

Slavery in Greece was a peculiar institution. When a city was conquered, its inhabitants were often sold as slaves.

Kidnapping boys and men in "barbarian," or non-Greek, lands and even in other Greek states was another

steady source of supply. If a slave was well educated or could be trained to a craft, he was in great demand.

An Athenian slave often had a chance to obtain his freedom, for quite frequently he was paid for his work, and

this gave him a chance to save money. After he had bought his freedom or had been set free by a grateful master,

he became a "metic"--a resident alien. Many of the slaves, however, had a miserable lot. They were sent

in gangs to the silver mines at Laurium, working in narrow underground corridors by the dim light of little lamps.

Although slavery freed the Athenians from drudgery, they led simple lives. They ate two meals a day, usually consisting

of bread, vegetable broth, fruit, and wine. Olives, olive oil, and honey were common foods. Cheese was often eaten

in place of meat. Fish was a delicacy.

The two-story houses of the Athenians were made of sun-dried brick and stood on narrow, winding streets. Even in

the cold months the houses were heated only with a brazier, or dish, of burning charcoal. The houses had no chimneys,

only a hole in the roof to let out the smoke from the stove in the tiny kitchen. There were no windows on the first

floor, but in the center of the house was a broad, open court, such as is found in Spanish and Oriental homes today.

Clustered about the court were the men's apartment, the women's apartment, and tiny bedrooms. There was no plumbing.

Refuse was thrown in the streets.

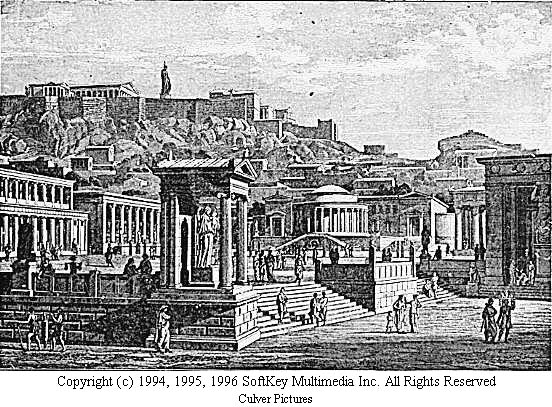

The Agora, or city center, of ancient Athens depicted as it may have looked in the Age of Pericles, was the gathering place and market center for citizens to shop, discuss affairs of state, and exchange gossip. --Culver Pictures

The real life of the city went on outdoors. The men spent their time talking politics and philosophy in the agora,

or marketplace. They exercised in the athletic fields, performed military duty, and took part in state festivals.

Some sat in the Assembly or the Council of 500 or served on juries. There were 6,000 jurors on call at all times

in Athens, for the allied cities were forced to bring cases to Athens for trial. Daily salaries were paid for jury

service and service on the Council. These made up a considerable part of the income of the poorer citizens.

The women stayed at home, spinning and weaving and doing household chores. They never acted as hostesses when their

husbands had parties and were seen in public only at the theater--where they might attend tragedy but not comedy--and

at certain religious festivals.

The growth of Athenian power aroused the jealousy of Sparta and other independent Greek states and the discontent

of Athens' subject states. The result was a war that put an end to the power of Athens. The long struggle, called

the Peloponnesian War, began in 431 BC. It was a contest between a great sea power, Athens and its empire, and

a great land power, Sparta and the Peloponnesian League.

The plan of Pericles in the beginning was not to fight at all, but to let Corinth and Sparta spend their money

and energies while Athens conserved both. He had all the inhabitants of Attica come inside the walls of Athens

and let their enemies ravage the plain year after year, while Athens, without losses, harried their lands by sea.

However, the bubonic plague broke out in besieged and overcrowded Athens. It killed one fourth of the population,

including Pericles, and left the rest without spirit and without a leader. The first phase of the Peloponnesian

War ended with the outcome undecided.

Almost before they knew it, the Athenians were whirled by the unscrupulous demagogue Alcibiades, a nephew of Pericles,

into the second phase of the war (414-404 BC). Wishing for a brilliant military career, Alcibiades persuaded Athens

to undertake a large-scale expedition against Syracuse, a Corinthian colony in Sicily. The Athenian armada was

destroyed in 413 BC, and the captives were sold into slavery.

This disaster sealed the fate of Athens. The allied Aegean cities that had remained faithful now deserted to Sparta,

and the Spartan armies laid Athens under siege. In 405 BC the whole remaining Athenian fleet of 180 triremes was

captured in the Hellespont at the battle of Aegospotami. Besieged by land and powerless by sea, Athens could neither

raise grain nor import it, and in 404 BC its empire came to an end. The fortifications and long walls connecting

Athens with Piraeus were destroyed, and Athens became a vassal of triumphant Sparta.

Sparta tried to maintain its supremacy by keeping garrisons in many of the Greek cities. This custom, together

with Sparta's hatred of democracy, made its domination unpopular. At the battle of Leuctra, in 371 BC, the Thebans

under their gifted commander Epaminondas put an end to the power of Sparta. Theban leadership was short-lived,

however, for it depended on the skill of Epaminondas. When he was killed in the battle of Mantinea, in 362 BC,

Thebes had really suffered a defeat in spite of its apparent victory. The age of the powerful city-states was at

an end, and a prostrated Greece had become easy prey for a would-be conqueror.

Such a conqueror was found in the young and strong country of Macedon, which lay just to the north of classical

Greece. Its King Philip, who came into power in 360 BC, had had a Greek education. Seeing the weakness of the disunited

cities, he made up his mind to take possession of the Greek world. Demosthenes saw the danger that threatened and

by a series of fiery speeches against Philip sought to unite the Greeks as they had once been united against Persia

(see Demosthenes).

The military might of Philip proved too strong for the disunited city-states, and at the battle of Chaeronea (338

BC) he established his leadership over Greece. Before he could carry his conquests to Asia Minor, however, he was

killed and his power fell to his son Alexander, then not quite 20 years old. Alexander firmly entrenched his rule

throughout Greece and then overthrew the vast power of Persia, building up an empire that embraced nearly the entire

known world (see Alexander the Great).

The three centuries that followed the death of Alexander are known as the Hellenistic Age, for their products were

no longer pure Greek, but Greek plus the characteristics of the conquered nations. The age was a time of great

wealth and splendor. Art, science, and letters flourished and developed. The private citizen no longer lived crudely,

but in a beautiful and comfortable house, and many cities adorned themselves with fine public buildings and sculptures.

The Hellenistic Age came to an end with another conquest--that of Rome. On the field of Cynoscephalae ("dogs'

heads"), in Thessaly, the Romans defeated Macedonia in 197 BC and gave the Greek cities their freedom

as allies. The Greeks caused Rome a great deal of trouble, and in 146 BC Corinth was burned. The Greeks became

vassals of Rome. Athens alone was revered and given some freedom. To its schools went many Romans, Cicero among

them.

When the seat of the Roman Empire was transferred to the east, Constantinople became the center of culture and

learning and Athens sank to the position of an unimportant country town (see Byzantine

Empire). In the 4th century AD Greece was devastated by the Visigoths under Alaric; in the 6th century it was

overrun by the Slavs; and in the 10th century it was raided by the Bulgars. In 1453 the Turks seized Constantinople,

and within a few years practically all Greece was in their hands. Only in the 19th century, after a protracted

struggle against their foreign rulers, did the Greeks finally regain their independence.

The glorious culture of the Greeks had its beginnings before the rise of the city-states to wealth and power and

survived long after the Greeks had lost their independence. The men of genius who left their stamp on the golden

age of Greece seemed to live a life apart from the tumultuous politics and wars of their era. They sprang up everywhere,

in scattered colonies as well as on the Greek peninsula. When the great creative age had passed its peak, Greek

artists and philosophers were sought as teachers in other lands, where they spread the wisdom of their masters.

What were these ideas for which the world reached out so eagerly? First was the determination to be guided by reason,

to follow the truth wherever it led. In their sculpture and architecture, in their literature and philosophy, the

Greeks were above all else reasonable. "Nothing to excess" (meden agan) was their central doctrine, a

doctrine that the Roman poet Horace later interpreted as "the golden mean."

The art of the Greeks was singularly free from exaggeration. Virtue was for them a path between two extremes--only

by temperance, they believed, could mankind attain happiness. Since this belief included maintaining a balanced

life of the mind and body, they provided time for play as well as work (see Olympic Games).

This many-sided culture seemed to spring into being almost full-grown. Before the rise of the Greek city-states,

Babylon had made contributions to astronomy, and the rudiments of geometry and medicine had been developed in Egypt.

The genius of the Greeks, however, owed little to these ancient civilizations. Greek culture had its beginnings

in the settlements on the coast of Asia Minor. Here Homer sang of a joyous, conquering people and of their gods,

who, far from being aloof and forbidding, were always ready to come down from Mount Olympus to play a part in the

absorbing life of the people (see Homeric Legend; Mythology;

Trojan War). Philosophy was also born in Asia Minor, where in the 6th and 5th centuries

BC such men as Thales, Heraclitus, and Democritus speculated on the makeup of the world. Thales also contributed

to the science of geometry, which was further advanced by the teacher and mathematician Pythagoras in the distant

colony of Croton in southern Italy (see Pythagoras).

The bronze mirror is from about the 6th or 5th century BC. --Alinari--Art Resource

In the 5th century BC, with the rise of Athens as a wealthy democratic state, the center of Greek culture passed

to the peninsula. Here the Greeks reached the peak of their extraordinary creative energy. This was the great period

of Greek literature, architecture, and sculpture, a period that reached its culmination in the age of Pericles

(see Pericles; Greek and Roman Art). Philosophers now

turned their thoughts from the study of matter to the study of mankind.

Toward the end of the century Socrates ushered in what is considered to be the most brilliant period of Greek philosophy,

passing on his wisdom to his pupil Plato. Plato in turn handed it on to "the master of those who know,"

the great Aristotle (see Socrates; Plato; Aristotle).

Alexander died in 323 BC. The spread of Greek learning that resulted from his conquests, however, laid the foundation

for much of the cultural progress of the Hellenistic Age. Alexandria, the city founded by Alexander at the mouth

of the Nile, became the intellectual capital of the world and a center of Greek scholarship. Its famous library,

founded by Ptolemy I, was said to have contained 700,000 rolls of papyrus manuscripts.

In literature and art the Hellenistic Age was imitative, looking to the masterpieces of earlier days for inspiration.

In science, however, much brilliant and original work was done. Archimedes put mechanics on a sound footing, and

Euclid established geometry as a science (see Archimedes; Euclid).

Eratosthenes made maps and calculated the Earth's circumference.

Aristarchus put forward the hypothesis that the Earth revolves around the sun. Ptolemy, or Claudius Ptolemaeus,

believed all the heavenly bodies circled the Earth, and his views prevailed throughout the Middle Ages.

The Hellenistic Age ended with the establishment of the Roman Empire in 31 BC. The Romans borrowed from the art

and science of the Greeks and drew upon their philosophy of Stoicism. As Christianity grew and spread, it was profoundly

influenced by Greek thought. Throughout the period of the barbarian invasions, Greek learning was preserved by

Christians in Constantinople and by Muslims in Cairo. Its light shone again in the Middle Ages with the founding

of the great universities in Italy, France, and England. During the Renaissance it provided an impetus for the

rebirth of art and literature (see Renaissance). Modern science rests on the Greek

idea of mankind's capacity to solve problems by rational methods. In almost every phase of life the quickening

impulse of Greek thought can be seen among the peoples who inherited this priceless legacy. (See also Ancient

Civilization.)

Amazon.com International Sites :